‘Pap’ Ruff and the Wheelmen’s Bench

by Joe Ward -- Semi-Official Club Historian

Some of you will recall that I ended the last installment with the tantalizing suggestion that Alloyce Black, a recent club president, arranged the first dedication of the Wheelmen’s Bench in Wayside Park. That bench, as some know, was built in 1897. That could mean I was suggesting that, barring involvement of the occult, Alloyce Black is at least 110 years old.

Many casual observers would doubt that, and, in fact, it’s not what I’m suggesting. I’m suggesting this: The Kentucky Division of the League of American Wheelmen spent a lot of time and effort planning and building the bench in the late 1890s, then never got around to formally dedicating it. So the ceremoney arranged by Alloyce in 1988, after extensive repairs to the structure may well have been the first dedication the thing ever had.

I scoured 1897 and 1898 editions of the Courier-Journal and Louisville Times on microfilm and found some information on the planning of the bench and on its construction. But just as a dedication was expected in May 1898, the Spanish American War pushed almost everything else out of the news for several months. I pored over both papers to the end of the year, noting with some dismay that bicycle news was getting less and less space, and failed to turn up any dedication of the bench. I intend to look farther eventually. But for the time being, it remains true that Alloyce gave the bench the first dedication I know about.

But I’m ahead of myself here. For the uninitiated -- and I see more of you on every ride -- the Wheelmen’s Bench is a limestone seat in a little park where Southern Parkway diverges from Third Street, not far from Churchill Downs. It has an inscription that says “Erected with the Approval of the Board of Park Commissioners by the Kentucky Division of the League of American Wheelmen in Memory of A.D. Ruff.” When I started riding with the club in 1977, nobody I could find knew who A.D. Ruff was, or for sure what the Roman numeral after his name was. It had been vandalized a little. It turned out to be 1897.

I checked the obit files at the newspapers, and old city directories, and couldn’t find any reference. I did find an old magazine called “Southern Cycler” at the Filson Club that reported in its December 1896 issue that the Kentucky Division was trying to decide what to do with a bequest from an A.D. Ruff. But cycling waned and the magazine folded before it ever said another word about it. I wrote a piece for the League’s Bulletin about the mystery. I heard subsequently from Jerry Crouch, a mainstay of the Bluegrass Wheelmen in Lexington. He said he’d seen language about the Kentucky Division of the League on a tombstone in the Owingsville Cemetery, up by Morehead. Guy named A.D. Ruff. Died Jan. 11, 1896. Crouch went to the Courier-Journal for Jan. 12, and found this obituary, on page 9 in the first section:

|

“Pap” Ruff Dead.

One of the Oldest Cyclists in the World

Left a Fortune, With No Heirs.

Owingsville, Ky., Jan 11 undefined (Special) undefined A.D. Ruff, a prominent citizen and one of the oldest and most enthusiastic cyclists of Kentucky, died of pneumonia at 11 o’clock this morning after an illness of a few days. Mr. Ruff, better known to wheelmen as “Pap” Ruff, was a native of Canada. He was 69 years of age and unmarried. He was a jeweler by trade and had been a resident of Owingsville for twenty years. When he came here, he had only a kit of jeweler’s tools. He leaves a fortune of from $25,000 to $40,000 in cash, with no known relatives. He was a fine mechanic, and the inventor and owner of many patents, which realized his fortune. “Pap” Ruff was one of the pioneer cyclists of the country. He was the oldest member of the League of American Wheelmen. About a year or so ago he made a journey awheel to Yellowstone National Park, a remarkable trip for a man of his years. |

So that’s who A.D. Ruff was. Myself, I wondered how much of that money the Kentucky division got. So I kept looking. The next reference I found was June 23, 1897. The Division was having its state meet in Cynthiana. Ruff had left the organization $1,000. The conference had decided to spend $200 on Ruff’s gravestone -- adding to that another $100 in division money -- and $800 on a “memorial fountain.” The fountain was to be erected somewhere on the Maysville Pike, between Lexington and Maysville. It was to be a place “where wheelmen may stop to drink and rest under the shade of the Forest trees.”

I found small chunks of the story, a line here and a paragraph there, through the next year or so. A small item a month later, incidentally, said $2,000 of Ruff’s money went to a son of Louis Schlegel of Richmond, who had been Ruff’s godson. But I never saw anything on any of the rest.

The Division named a committee to work on the memorial -- Ed Croninger and John Clendening of Covington, J.J. Nesbitt, of Owingsville, and W.W. Watts and G.E. Johnson, of Louisville. Johnson had an office in the Courier-Journal Building, now the Morrisey Building, where the Louisville Chamber of Commerce is. The papers didn’t say what he did for a living. But Watts and Johnson were named to a location subcommittee.

Oddly enough, the Maysville Pike had been ruled out as a location by July 25, and the new plan was to build the memorial on a “Boulevard” somewhere in Louisville. “Ruthless vandalism” by “tramps and hoodlums” out in the countryside were given as the reason. Two locations were suggested: The Chestnut St. Boulevard near the entrance to Shawnee Park, and a spot “on the triangle of ground just south of the little school house on The Boulevard (as Southern Parkway was known in those days), just after leaving the brick.” The Board of Park Commissioners, then headed by Gen. John Breckinridge Castleman, was to decide. By Sept. 12 they had picked Southern Parkway and work began.

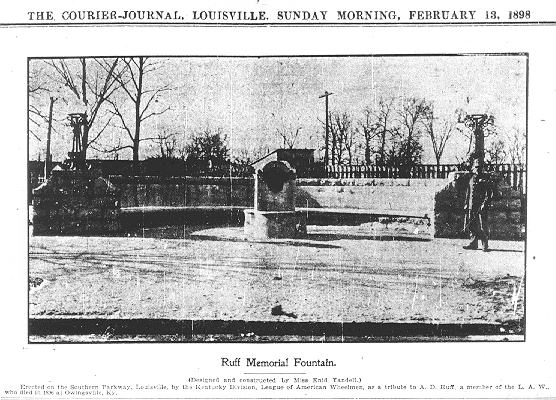

An August 1 Courier-Journal story said “Enid Yandell” would design the memorial, and a Sept. 11 piece in the Louisville Times said “Miss Enid Fendell” had been awarded the contract to build it. I assume they were the same person, but neither name was mentioned again. Groundbreaking was reported Sept. 25, and construction was “well underway” by Oct. 8. Completion was expected by Oct. 15.

A Nov. 18 piece said the bench was “almost complete,” and was a “handsome piece of work.” A Jan. 17, 1898, story said it was complete and would be dedicated “in early spring.” The Courier reported Mar. 27 that it was “in use” and would get “lights and water when the season opens.” The Iroquois Wheeling & Dining Club formally opened cycling’s social season April 30, an event duly noted by the press. But the story said dedication of the memorial was still a couple of weeks off. There the trail ends. Neither the Courier nor the Times mentioned the bench again in 1898.

Meanwhile, back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the kind of vandals Watts and Johnson had warned about on the Maysville Pike showed up in Louisville. Stones began disappearing, opening the bench to weather. In 1982 Bill Parish, maintenance superintendent for the Metropolitan Park and Recreation Board, ordered the bench torn down and rebuilt. Park employees replaced some stones, but left the battered inscription as it was. That restoration lasted about two years.

In 1984 the club took up the cause of bench restoration, almost immediately with the idea of rededicating it to Wallace “Sprad” Spradling, a former club president who had pursued the idea of a velodrome for Louisville as knights-errant did the grail, dying, as they did, without success. He also was like Ruff in that he was the oldest cyclist any of us knew of, and he astonished us by getting around on a succession of strange machines. He died in May 1984, at 78.

Alloyce was secretary of the club when the effort started, and she remembers that Chuck Black, John Rice, Maynard Stetton, and Mike Schneider, among others, were involved. Chuck called Bill Brummett, of Brummett Monument in New Albany, who hoisted out the big seat slabs and the inscription stone and hauled them across the river for storage. Little did he know they’d be there three years.

Mike Schneider actually got a rebuilding effort underway, but the stone turned out to be the wrong kind. The neighbors objected and the city intervened, and the search was on for a certain kind of limestone. It was widely used in Louisville foundations, but none we could get our hands on for a long time.

Finally, Alloyce got a call from Charlie Donohoe, of Charlie’s Wrecking, who had heard what we needed, and thought he had it where he was tearing down the old Green Mouse Cafe, at Third and Winkler. That’s very near the bench, and the stone was right. “I knew it was right,” Alloyce said. “I’d looked at enough stone.” But the city had to approve it, and it had to be off the wrecking site by that night. Charlie agreed to haul it to his farm in Indiana and store it.

Next Alloyce found Tom Johnson, of Keystone Restorations, a man who could do the masonry. The city ultimately got a $2,500 matching grant to do the work, but not Donohoe, nor Brummett, nor Johnson got any of the money. Their labor was the club’s contribution for the matching. “Each did a herculean task and charged nothing,” Alloyce said.

They put the poor old bench back together, complete with the inscription rechiseled, and a rededication to Sprad added. With help from Larry Hammers and others, Alloyce got Mayor Jerry Abramson, County Judge Harvey Sloane and 100 wheelmen, among others, out for a ceremony. Irene Spradling, Sprad’s daughter took part. Chris Engleman, who is nearly as old as Sprad now, showed up on a high wheeler. Tom Owen, who was not yet an alderman, gave a talk on the history of the site. There was music, some balloons, some hot spiced cider and cookies. It was a wonderful October day, the 30th.

And as far as anybody knows, it was the only dedication the bench has ever had.

Wheelmen’s Bench as it was in 1898.

| This article is part of a series about the history of the Louisville Bicycle Club (formerly the Louisville Wheelmen) by Joe Ward, a long-time club member. The series originally appeared in the club’s newsletters in 1988-1989. |